November 30, 2024

What’s With Canada’s Judicial Amnesia?

October 5, 2024

HERE'S MY TAKE

When Richard Wagner, the Chief Justice of the Supreme Court of Canada, argues that pre-1970 Supreme Court decisions are of “minute” value and are just part of “our legal cultural heritage” it’s nothing short of startling. When he says that “no one today [would] refer to a precedent from 1892 to support their case” it alarmingly gives legal precedents a shelf life. No wonder the three law professors who brought these comments (delivered in June and in French) to the public’s attention found Justice Wagner’s words “astonishing.”

The online reaction was swift. Admittedly, much of it muddied the details of what Justice Wagner actually said, given that he was answering a question about how many resources should be dedicated to translating court decisions published before the Official Languages Act was passed. But the central point seemed near unanimous: he was reflecting a view of law that did not place great value on tradition and history, preferring to think of the 1982 adoption of the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms as “year zero” in defining what rights and freedoms mean for Canadians.

Law does not belong to lawyers and jurists; it’s ordinary folk without legal training for whom the law is supposed to be both a shield to protect from others’ intrusions into our lives (with governments being the usual culprits) and a sword to enable us to express ourselves. One of the earliest Supreme Court of Canada judgements after the adoption of the Charter, R. vs. Big M Drug Mart Ltd., summarized it this way: “Freedom in a broad sense embraces both the absence of coercion and constraint, and the right to manifest beliefs and practices.”

Most non-lawyers don’t use Latin terms too frequently, but I’ll mention one: stare decisis—“to stand by things decided.” It reflects an understanding of our basic framework in which the legislature passes laws. When there is an allegation that someone has violated a law, the court has the jurisdiction both to weigh the evidence (determining what actually happened that broke the law) and to apply the law (determining how the facts align with what the text of the law requires and what should be done about it). The understanding is that once a court decides something, it becomes precedent and that similar cases will be decided in a similar manner. That’s what “ordinary citizens” expect from the courts.

A few weeks back, I attended a Christian Legal Fellowship conference called “The Shape of Freedom.” The presentations, mostly from judges and law professors, focused on various dimensions of freedom. For example, Osgoode Hall Law School Professor Jamie Cameron argued that Section 2(c) of the Charter of Rights guaranteeing “freedom of peaceful assembly” has to date been “a dead stump in the charter forest of living trees.” It’s not that the issue isn’t current: the freedom convoy, university protests regarding the Hamas-Israel conflict, and homeless encampments have provided a multitude of legal cases in which our understanding of assembly and protest are key. But, as Professor Cameron noted, these cases are being decided without a coherent framework as to what Section 2(c) promises. Given that the right to assemble is a social right, bringing along with it the right to associate and express, it implies a right to disrupt others in order to bring attention to someone’s concerns. Professor Richard Moon noted that the right to express oneself “connects the individual to a group” and that the right to peacefully assemble not only is “instrumental” in determining what an individual is free to do but also “intrinsic” in giving meaning to human agency and dignity. The problem is that the courts have been “balancing” when rights come into conflict rather than developing a deeper understanding by which Canadians can understand what their rights actually are.

This sounds esoteric but has huge practical consequences for everyday life. As panelists pointed out, in the absence of clear law we get the social confusion we’ve experienced of late on various issues. A group of citizens is concerned about an issue and decides to assemble in protest. That right is clear, but does that mean they get to occupy the lawn of city hall, a university campus, or the street in front of Parliament indefinitely? We’ve mostly tried to regulate this with administrative rules—“you need to get a permit”—but as political issues intensify, administrative rules lose their impact. So now the issue is dealt with as a policing strategy and, for the most part, the pattern is to “let them protest.” Public safety rather than legal rights become the standard and as long as nothing egregiously unsafe or criminal happens, we ignore a host of more mundane laws (like parking violations) that happen in the course of the protest.

All of this occurs regularly which, I suppose, is why protests end up intensifying. Becoming even more disruptive seems to be the best way to make a point and hopefully get movement towards some desired change. But at some point, all of that expression and assembly starts to disrupt the lives of other citizens. Eventually, those citizens take (or call for) legal action. The police use trespassing or noise and parking laws (all proper in their own place but really incidental to the bigger picture) to try to disperse the assembly. Increasingly of late, police are also relying on court injunctions or the very controversial suspension of freedoms through measures like the Emergencies Act. The prosecutions of cases after the event seem very inconsistent. Many of the charges are quietly dropped after the event, but authorities pursue a few to great lengths, which some see as politicized show trials meant to make examples of the organizers.

There are several aspects of the constitution that are similarly muddy in their application to everyday life. On the one hand, a country with a constitution that is less than 50 years old might expect that. On the other hand, the 1982 repatriation of the constitution did not begin things in Canada. We’ve had a constitution since 1867 (which assumed the relevance of British common law that preceded it) and a Bill of Rights since 1958. The Charter of Rights and Freedoms was not introduced to replace any rights but rather to clarify and augment them; all of the rights that Canadians had on April 16, 1982 they continued to have on April 17th after the Queen signed the document, even if the document defined and framed those same rights somewhat differently.

This brings us back to Justice Wagner’s comments. I’ll grant him a bit of leeway because he was answering a question about the application of the Official Languages Act and the implications (and costs) of translating pre-1970 Supreme Court judgements. But answers about specifics are indicative of a broader framework of thought. It is clear that Justice Wagner is more convinced about the wisdom of the judgement of the current bench than he is about the value of history. We shouldn’t be surprised. The Supreme Court of Canada is quite ready to declare itself wiser than history, even after 1982, when interpreting the same text. In 2001, the court ruled the Charter protected Trinity Western University’s right to have a community standards agreement and to have its graduates certified as teachers. In 2018, the court ruled that the same Charter determined that the same community standards agreement was unconstitutional, making it impossible for TWU to have a recognized law school since it would be inherently discriminatory. A similar about-face took place regarding the requirement of the state to offer euthanasia as a matter of constitutional rights, which in 1993 was not required, but in 2015 it was.

Law is complex, but if it is to be a meaningful articulation of our freedoms, both negatively and positively, it needs to be predictable, stable, and developed by accounting for, not setting aside, our history. Whether we need to have “official” French translations of historic Supreme Court decisions might be debatable, but the diminishment of our history is a much more serious matter. An apparent willingness to make whatever legal contortions are required to ignore precedent and conform to the prevailing cultural winds ends up making our constitution the opposite of what it should be and diminishes rather than enhances freedom.

To be sure, there is a balance between applying legislative intent and adapting a document to be read in a present context. But the suggestion that legal history has only “minute” significance confirms a mindset that many critics of Canada’s courts have worried about. In the same media conference, Justice Wagner argued that public trust is “essential to the rule of law.” The rule of law values history and learns from it. The court needs to be a protection against the cultural arrogance of our present moment, which sees the past as irrelevant and claims we can redefine reality as we want.

WHAT I’M READING

Media Marketing Bias

CTV’s production of doctored video to support its Sunday Magazine story on the Conservative non-confidence motion last week, has been the subject of wide debate. Harrison Lowman, who has worked in many TV studios, including the CTV one where this now infamous segment was produced, argued this incident was unlikely a conscious conspiracy. Rather, he contends, the combination of budget cuts and lack of viewpoint diversity in the newsroom meant a glaring problem went unnoticed. Peter Menzies observes that it may be television marketing practices as much as lack of editorial rigour that led to the production of this erroneous video.

The Problem of Pornography

I grew up in an era where pornography was commonplace. It was impossible to ignore given the prominence of the titles in plain view on every magazine rack. However, it was also difficult to access because it was on paper behind opaque barriers. Social media and the internet have changed how we come across porn, even when we don’t seek it out. Sadly, the social effects of this are everywhere. A shocking 12% of all websites are dedicated to pornography, as Daniel Cox highlights in this essay. He argues that there is increasing social confusion regarding how moral principles apply to porn and its distribution.

Trudeau Wants a Vote on his Values

Prime Minister Trudeau argues the next federal election will be a values-based fight – that’s what he told a Liberal MP in a podcast interview recently. Paul Wells was listening, and now he’s taking two substack essays to reflect on Trudeau’s remarks. Both the summary of the prime minister’s thoughts as well as Wells’ analysis provide an interesting take on Trudeau’s mindset, which notwithstanding all of the other issues and political drama, remains the most significant variable in the timing and framing of the next federal election.

MAiD in the Courts

A coalition of disability rights groups is suing the federal government over euthanasia. The group argues that by providing a second track for euthanasia which removes the prerequisite of a “foreseeable death” from the eligibility criteria, the government is placing pressure on those with disabilities to seek death in the absence of requisite basic social supports. Readers in the Hamilton area may be interested in an event on Tuesday evening where I will be moderating a discussion with experts regarding “Vulnerable Lives at Risk: A Critical Look at MAiD in Canada.”

MEANINGFUL METRICS

You Disagree How?

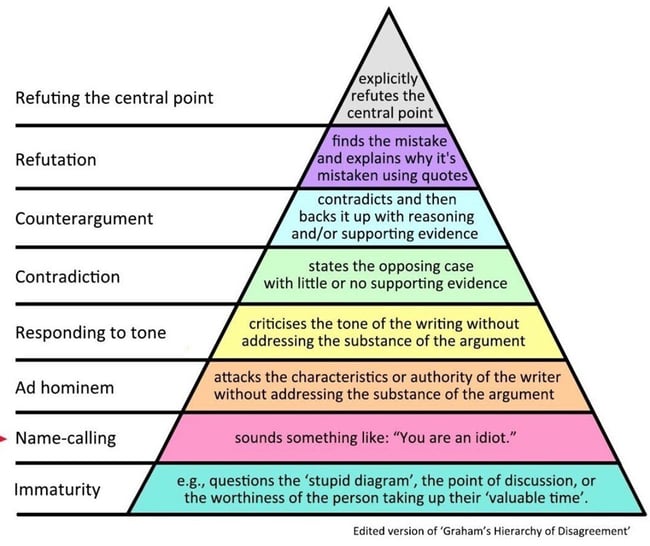

I’ve spent much of the week in convention with my Cardus colleagues and, given our vocation, the matter of disagreeing well is always a subtext of the conversation. Graham’s Hierarchy of Disagreement came up as a useful reminder of how to approach argumentation. It’s not easy to measure precisely, but it would seem that immature name-calling is most of what passes for public disagreement these days. Sadly, it seems the useful techniques of pointing out contradictions, making counterarguments, and refutation are in shorter supply. We’d all do well to improve our skills in distilling disagreements to refuting a central point while articulating, naming, and countering what is really in dispute.

TAKE IT TO-GO

OK, It's Corny

If modesty were not a desired virtue, I would’ve headlined the fact that the team captained by the oldest guy on staff won gold medals in the prestigious Cardus Staff Lawn Olympiad this week. There would be more than a kernel of truth in observing that capability in the corn-hole toss contributed to a gold-winning performance for the four-person Team 2. (Unlike the marketing folk who had fancy team names and chants but did not win, we had the financial controller on our team. So, we remained rooted in reality and just delivered the winning crop on budget and in the gold.) We had the advantage of half our team being from the West. And, yes, you’d be right in assuming Albertans and Iowans know their corn types well. You might just say we embraced my farming roots and were outstanding in our field. Truthfully though, farming isn’t on any of our resumes: we are a hybrid team of think-tankers and competitors with amaizing resilience.

Before I have to field any questions about why the end of this newsletter stalks you with corny wordplay (even when it is contrived to pass on the news of a bumper medal crop) take comfort that next Saturday comes during Thanksgiving weekend in Canada. Insights doesn’t publish on long weekends, so instead of husking whatever corn puns come to mind, let me just wish you a delightful Thanksgiving celebration. We appreciate your interest and support and look forward to being back in your inbox in two weeks’ time.

Reply to Ray